IWRAW Asia Pacific: ‘Wages For Caring Work’: An Exploration Of The Care Income Campaign

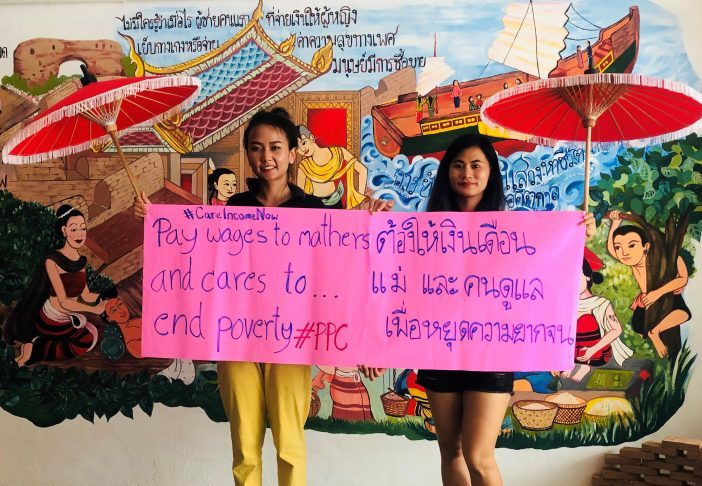

In this interview, IWRAW Asia Pacific asks two activists based in Thailand about the concept of care income, its history in the women’s rights movement, and its role in building gender-just post-COVID-19 economies. Liz Hilton works with Empower Foundation, a sex-worker-led advocacy organisation in Chiang Mai, and Bee Pranom Somwong works at Protection Desk Thailand, supporting local grassroots initiatives and human rights defenders in rural and semi-rural areas. Both are part of a Community Women Human Rights Defenders (WHRD) Collective in Thailand, of about 40 WHRDs working at the community level and representing about 19 different sectors and thousands of other women in their communities.

In March 2020, the #CareIncomeNow campaign published an open letter to all governments demanding care income “across the planet for all those, of every gender, who care for people, the urban and rural environment, and the natural world.” What is care income and why do you support it?

For centuries, nations, societies and cultures have relied on the unwaged work of people, mainly women, to ensure that the young, the elderly and others unable to fully care for themselves are looked after. Society has relied on unwaged caring work to ensure that successive generations are produced, educated, and socialised. Nations depend on unwaged caring work for the existence, health, and well-being of their waged workforce. Three quarters of the world’s unwaged caring work is done by women undertaking 12.5 billion hours every day and representing a contribution to the global economy of at least $10.8 trillion a year.

Care income describes an end to this system. It describes a wage, paid in cash or access to land, beginning with mothers and other primary carers, and including those who care for and protect the soil, water, air and natural world. The care income values and recognises the life-giving and life-sustaining work of reproducing and caring for the entire human race. It recognises caring as fundamental to all human relationships and the need to invest in those who do care work for the survival of us all. It recognises that there is no human reproduction without the natural world on which we all depend – the care of the land, the air, the oceans and the rivers. It demands a reversal of priorities: from an economy aimed at profit which enriches some to the detriment of all, to an economy aimed at protecting and enriching all life.

The demand for a care income has grown out of the International Wages for Housework Campaign (IWFHC) started in 1972 by Selma James. The IWFHC is an ongoing campaign that begins with those with least power internationally – unwaged workers in the home, mostly mothers, and unwaged subsistence farmers and workers on the land and in the community. The demand for wages for caring work is also a way of organising from the bottom up, of autonomous sectors working together to end the imbalance of power relations among us. The IWFHC succeeded in getting the UN to pass path-breaking commitments that acknowledge the contribution of unwaged caring work that women do in the home, on the land, and in the community. Since 8 March 2000, the IWFHC has become more widely known as the Global Women’s Strike (GWS).

When did you first become involved with the campaign? Has the Covid-19 pandemic affected your views on care income?

Sex workers of the English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP) had been a part of the IWFHC since 1975. In 2015 ECP introduced Empower to the IWFHC and connections were made with the Community WHRD Collective in Thailand.

In our collective only a few receive any wages for the work of defending human rights. More than half of us are mothers. Our average working day is 14 hours, though only six hours is waged work, e.g. rubber tapping, sex work, motorcycle taxi, or sewing. We care for the family, are core members of our community struggles, and many of us also care for the natural resources around us. This is important work. It makes perfect sense to us that since everyone else is paid for their labour, we also must be paid for our work.

The COVID-19 pandemic has laid bare many of the cracks, injustices and inequalities in the world. It has also made clear that governments everywhere are dependent on mothers and other carers, mostly low-waged and unwaged, to ensure the survival and protection of families and communities. Governments and other agencies have also struggled to find ways to provide practical assistance and relief to the people. In many places it is a logistical nightmare that remains unsolved months into the pandemic. Had a care income been in place, families and communities would have had better food security and a safety net. Had a care income been the norm, governments would have been able to use existing payment systems to provide increased relief. Instead, many of the poorest families and communities are left devastated by loss of income, facing hunger, homelessness, and despair. It has also shown that money which could never be found before suddenly became available along with rent forgiveness, healthcare, etc.

What strategies are you and the Community WHRD Collective using to advocate for care income in Thailand? Are there any regional activities happening in support of care income?

Care income, though straightforward in its demand, has many layers and nuances. Our first work is to explore this together, so we are more confident and able to speak to the many issues it raises. Our own relationships in our families and communities will be changed by the care income and this needs to be looked at and planned for. This will be ongoing work as we create the opportunity to raise the care income in all forums and spaces and meet more and more women who find it interesting and exciting.

Secondly, we are working to have the care income adopted by We Fair, the civil society network for state welfare in Thailand. We will be focusing on the child support grant here as the first financial recognition of caring work paid by the State.

The current Thai constitution is controversial and will be under review. Our collective has submitted the call for a care income to be part of any new constitution amendments.

Has care income been accepted by countries or organisations outside the region?

Even in the region we are not starting from zero. The work of caring that we do for strangers outside the home is waged, even though underpaid, as cleaning, washing, cooking, childcare, domestic work. This is an acknowledgment that caring is work. In addition, the paying of maternity and/or paternity leave, child support grants, carer’s allowance, payments for foster parents, single mothers’ benefit, access to public land for farming, and social housing are all evidence that there is wide acceptance by many governments that those caring for others in the family need and deserve financial support. These payments/benefits can be counted as components of a care income, and the work of making this visible is part of campaigning for it. Of course, these payments urgently need to be amalgamated, redefined as wages and most importantly increased both in amount and reach.

A concrete example of policy can be found in Hawaii where the Kupuna Caregiver Assistance Act was adopted in July 2017. It pays up to $70 a day to eligible working family members to care for their ageing loved ones at home.

Two countries of note have gone further in including the value of the work done in the home in their constitutions:

Constitution of Venezuela Article 88:

The State guarantees equality and equity between men and women in the exercise of their right to work. The State recognises work at home as an economic activity that creates added value and produces social welfare and wealth. Housewives are entitled to Social Security in accordance with the law.

Constitution of Ireland Article 41.2(note: the language in the Constitution of Ireland is outdated and under review):

The State recognises that by her life within the home, woman gives to the State a support without which the common good cannot be achieved. The State shall, therefore, endeavour to ensure that mothers shall not be obliged by economic necessity to engage in labour to the neglect of their duties in the home.

In Peru, where domestic workers have won legislation ensuring their rights as workers, mothers in our network are campaigning for a care income. They point out that they often have to leave their children on their own in the city, or to emigrate from the village to the city without their children in order to care for other people’s children. They say: “What about our families!” It’s the same for women in Thailand.

Has the #CareIncomeNOW campaign encountered concerns relating to the risk of reinforcing gender stereotypes?

This concern has been raised since the WFH campaign began in the 1970s, though the language has changed (e.g. ‘risk of institutionalising women in the home’). Of course, we must always be alert to co-option by the State and other actors for their own gain. The reality however is that pregnancy, giving birth, breastfeeding, housework and caring for family is mostly done by women. Better-off women pay other women, often migrant women, to do this work for them. We think that the care income can lay plain the current reality of institutionalised gender roles, and at the same time begin to reduce the power imbalance between us, whether that imbalance springs from sex, race or class. We think more men and other genders will be willing and able to do the work of caring for family and the planet if it is waged and valued by society.

What is the difference between care income and universal basic income (UBI)?

The UBI is an initiative that provides an income for people, some or all depending on the schemes, to be able to survive even if they don’t have a paid job. We worry about any government initiatives which include the word ‘basic’, as it usually means extremely basic indeed. Mothers and other carers who get the UBI would still be doing the work of caring for others. The UBI does not recognise or compensate for the unwaged work of caring. It does not contribute to valuing care for people and the planet. It does not increase the status of the mainly women who do this work, and, therefore, does little to end the unequal power relations among women and men, as well as among women. Regardless of whether the UBI is or is not a useful initiative, the care income must come first and must be paid on top of any UBI. In a similar vein, elderly or disabled people who care for their children, partners, grandchildren, or others must receive the care income on top of any existing welfare benefits, such as aged pensions and disability benefits. Care income for the care of others and the natural world; welfare for the extra needs of caring for oneself; and UBI to ensure everyone’s right to life.

What advice would you give to people interested in advocating for care income in their countries? Are there other resources they can review to learn more?

It is good to begin with making clear to everyone the unwaged work that women and others are doing, starting with ourselves and the women around us. Some countries count this work in their national statistics (though most do not) and so does the UN. Look at what ‘care income’ the State is already providing, like child support or maternity leave, and how it could be extended and reframed. For further reading and connections, the GWS has a treasure trove of information on the care income and the Wages for Housework Campaign. In February 2021, a new anthology, called Our Time is Now: Sex, Race, Class and Caring for People and Planet, will be released that includes the latest papers on the Care Income Campaign by Selma James and the GWS. The Green New Deal for Europe and the Poor Peoples’ Campaign in the US are two large movements which have included the call for a care income in their platforms.

See also:

- Chia, J., The Cost of Opposing Mines in Thailand’s Rural Heartland, Thai Enquirer, 2020.

- Empower Foundation, ‘Sweet, Smart, Strong and Sexy’: The Sex Workers Taking a Stand in Thailand, openDemocracy, 2020.

- IWRAW Asia Pacific, Care is an Economic Issue: Addressing Gender Inequalities in Care Work, 2018.

- IWRAW Asia Pacific, Four Things to Know about the Purple Economy, 2018.